by Kathleen Cross | Dec 20, 2010 | activists |

I really don’t know what to think of this Julian Assange WikiLeaks debacle. With the exception of those who have already judged and convicted the man, people seem to be afraid to write or say what they think for fear of having their words sifted through the NSA’s supersifter translator anti-anarchist thingy. So, unless you’re counting filmmaker Michael Moore who apparently doesn’t give a damn what the NSA thinks of him, cautious folks are just sort of talking and whispering about the story in headlines and soundbites.

“…what if the public in 2003 had been able to read “secret” memos from Dick Cheney as he pressured the CIA to give him the “facts” he wanted in order to build his false case for war? If a WikiLeaks had revealed at that time that there were, in fact, no weapons of mass destruction, do you think that the war would have been launched…?” -Michael Moore

I wouldn’t really categorize myself as a conspiracy theorist, but I do believe that just as governments “have ways of making you talk,” they also have ways of making you shut the f*#% up. I’m trying to use my intellect and intuition to arrive at some sort of personal opinion about Assange’s motives, and his recent alleged criminal behavior, but I’m finding that it is difficult to uncover much unbiased information in this age of pseudo-journalistic news coverage.

I did search the Internet and found some interesting back story that I wasn’t aware of. Although it’s been well-reported that Assange was convicted of computer hacking when he was a teenager, not much else about his character is widely known. I was able to find a CNN affiliate’s exclusive December 2nd interview with Julian’s father Brett Assange, where it was revealed that Julian was always “the kind of kid that wouldn’t take no for an answer. ” I suppose those who believe the rape allegations will take that and run with it, but from all that his dad says about him, it seems Julian could easily be the target of a smear campaign.

“He always stood up for the underdog…He was always very angry about people ganging up on other people. He had a really good sense of equality and equity.”

Julian’s mother also sees her son as a champion of right and wrong. She told the Melbourne Herald Sun that she saw in him from a tender age a sensitive boy who was good with animals and had an innate will to do “what he perceived as just.” In another interview with the U.K. Mail she said:

‘My son is a good person who is doing good for others. He wants people to know the truth. People have a right to know what is going on, especially if a war is being fought in their name. The people who have committed atrocities should be the ones called to account, not my son….He’s a hero to some people, a villain to others. Which one do you think I believe?”

Of course those are his parents, so if I’m looking for unbiased information, I’ll have to keep looking. Where do I find someone unrelated to him to serve as a character reference? I’m not finding quotes on the Internet from regular folks attesting to his integrity (perhaps due to the aforementioned sifter thingy), but Amnesty International did recognize him for “excellence in human rights journalism,” and he has supporters around the world who post bail money when needed, and demonstrate with signs that read “COURAGE is COURAGEOUS” and “DON’T SHOOT THE MESSENGER.”

Conversely, finding quotes from individuals who clearly don’t care for the man hasn’t been difficult. We know there are two women in Sweden who have accused him of sexual assault, serious charges which will he will have to answer to in a court of law. Assange says he is innocent and the women are a part of well-orchestrated smear campaign–a covert attempt by the powers that be to silence his website. Along with these serious charges against him, Assange has made himself a pretty impressive list of enemies–and this is but a tiny excerpt of what is a very long list:

WikiLeaks “has violated the Espionage Act.” -Sen. Joe Lieberman

“super-secretive, thin-skinned, [and] megalomaniacal.” –The New Yorker‘s George Packer

“an anti-American operative with blood on his hands” whom we should pursue “with the same urgency we pursue al Qaeda and Taliban leaders.” -Sarah Palin

“He’s a psychopath, a sociopath … He’s a terrorist.” -Republican Mary Matalin

“A dead man can’t leak stuff … there’s only one way to do it: illegally shoot the son of a bitch.” –Democrat Bob Beckel

That last quote makes me think of David Kelly, the U.K. biochemist and U.N. weapons inspector whose off-the-record comments (he said the government exaggerated about WMD in Iraq) led to his death. Though officially dubbed a suicide, Britain’s Michael Powers, a physician, barrister, and former coronor has joined a group of physicians and others who don’t believe the evidence supports the suicide finding. Lord Hutton decided that evidence related to the death, including the post-mortem report and photographs of the body, should remain classified for 70 years.

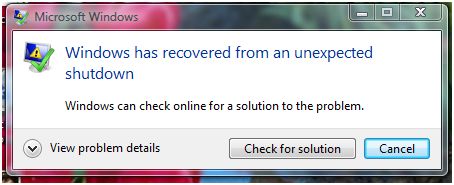

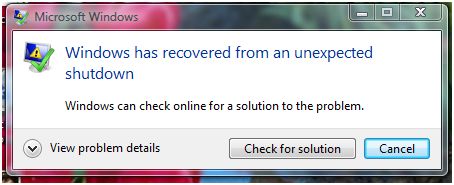

Whoa… Okay. I’m not making this up. My computer just crashed to the dreaded BLUE SCREEN fatal exception error. This was on my screen when I rebooted:

Allrightee then. I’m sure that was just a coincidence. Okay NSA, I am not trying to get on your list please.

Allrightee then. I’m sure that was just a coincidence. Okay NSA, I am not trying to get on your list please.

Aaaaaaanyway,

I think it is completely possible that Julian Assange committed the crimes he is accused of, and if he did, I don’t see how that should have a bearing on whether WikiLeaks is deemed to be journalism, civil disobedience or out-and-out terrorism. Let the world’s courts open up that discussion–not the tabloids.

I also think it is completely possible he had consensual sex with those women, and someone has either enticed or coerced them to lie about it. Either way, the debate will continue to rage about whether Assange is a terrorist or a whistle blower and if WikiLeaks’ brand of “transparency” hurts more than it helps.

“Our goal is to have a just civilization. That is sort of a personal motivating goal. And the message is transparency…we believe that it is an excellent message. Gaining justice with transparency. It is a good way of doing that, it is also a good way of not making too many mistakes. We have a trans-political ideology, it is not right it is not left it is about understanding…any political ideology that comes out of misunderstanding will itself be a misunderstanding. So, we say, to some degree all political ideologies are currently bankrupt. Because they do not have the raw ingredient they need to address the world. The raw ingredient to understand what is actually happening.” -Julian Assange

All of that sounds really good to me because I agree with his assertion that the existing political ideologies are bankrupt. The truth is, regardless of the continents we live on, the names we use to call on the Creator, or the political ideologies we profess, none of us want our cities to be incinerated. I do feel like governments might be less likely to commit crimes against humanity if they know they are being observed, but I don’t feel I have a full understanding of what kind of havoc such transparency can wreak either.

Is Julian Assange a dangerous devil, or a courageous daredevil? My intuition leans me toward the latter, but I’d like more solid information to help me decide.

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 18, 2010 | celebrities, musical artist, they give, young people |

When a dozen cars filled with police investigators pulled up at the gates of Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch seven years ago, it’s as if they brought along some kind of Dr. Evil-inspired device that could suck every last bit of magic out of a place. Though Michael remained there throughout his trial, once he was acquitted of all charges he and his children left their Neverland home and never went back.

My daughters and I spent two amazing days at the ranch just four weeks prior to that raid, and I can tell you first hand there isn’t another place on earth quite like it–as it used to be, that is. We rode the amusement park rides, played in Michael’s incredible game room and enjoyed an awesome concert put on by the organization “Oneness” in honor of artist Romero Britto. We slept in a guest room above the movie theater where Michael had designed glass-fronted rooms with hospital beds where terminally ill children could experience the magic of being at the movies (while they were hooked up to the tubes and machines needed to keep them alive). The movie Seabiscuit was playing the night we were there.

Our two days at Neverland were filled with way too much magic to describe here, but I can confirm reports that there were ice cream carts everywhere, and yes, an endless supply of candy and popcorn free for the taking. One of the highlights of the visit for me was sitting in an open field with Michael’s orangutan Brandy who developed a little crush on me and wanted to share a can of Coca Cola. (No it wasn’t Pepsi, and I had to pretend to drink from it or risk hurting her feelings.)

Today, TMZ is reporting that Colony Capital, who now owns the property, wants to turn Neverland into a music institute — similar to The Juilliard School in NYC where teens of diverse backgrounds will live and learn all aspects of music, including writing and performing. Wow. Of all the rumored possibilities we’ve heard for Michael’s once-beloved retreat, I can’t help but believe he might most approve of this one. What better way to honor the greatest entertainer who has ever lived, than to turn his once magic kingdom into a place where young people can go to develop their musical gifts.

The world will certainly benefit if Michael’s “Giving Tree” inspires more of the incredible music he says it inspired in him.

“God gave us talent to give; to help people, and to give back.” -MJ

You can read TMZ’s exclusive story here.

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 17, 2010 | Uncategorized |

[slideshow]

For almost two years a mysterious tweeter with the username @HolyWords (aka “Soul Food”) has been blessing the timelines of its 20,000 followers with 140 characters of daily inspiration…and now suddenly they’re not.

I know what you’re thinking. So what, there’s like a go-zillion tweeters cluttering up the twitosphere with quotes meant to inspire us to become higher life forms. And, you’re right. Puh-leeze, just enter the word “quotes” in the Twitter search box and you’ll get a username list too long to scroll to the bottom of. These well-meaning tweeters really do have some good stuff to share too, but you also get to wade through a sea of mind-blowing spiritual epiphanies such as “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels,” “A parent is only as good as their dumbest kid,” or “Don’t drink the pee-pee” (Thank you IamDiddy for blessing my timeline with the word “pee-pee” like 17,455 times this year.)

The beauty of @HolyWords was its unique, succinct, minimalist way of sharing some pretty deep life advice, and asking the world and its religions to get along at the same time. Not by bombarding us with fifty messages a day, but with just one–one thought of the day from a variety of holy books. A thought which, if pondered and acted upon, really would make us and the world just a bit better than we were the day before.

@HolyWords last tweeted on November 2nd and we haven’t heard a peep out of ’em since.

So, I’m thinking maybe researching the world’s religions and posting a short but meaningful spiritual snippet every day just got to be a little overwhelming. Maybe the holy tweeter started feeling like nobody really cared if they silenced themselves forever. Maybe they are in the hospital or in jail. Maybe they’re an unemployed 99er and can’t pay the DSL bill. Maybe they joined a monastery and have taken a vow of silence. Or, maybe @HolyWords is simply in need of a little appreciation and inspiration, and they’ll get right back to sharing.

Believing it’s the latter, I would like to share some reasons why @HolyWords should tweet again:

1. @HolyWords has landed on the following lists:

- Top 20 Most Inspirational People on Twitter (Listorious.com)

(Also on that list are Tony Robbins, Deepak Choprah, Michael Beckworth and Ekhart Tolle)

- Twitter’s Top 40 Most Influential (WeFollow.com)

- Twitter’s Top 3 Scripture (WeFollow.com)

- Top 1% of all retweeted tweeters (of Twitters 200 million users)

2. @HolyWords has been added to more than 500 individual Twitter member’s own lists. These are lists with names like:

- rare-tweet-garden

- in-need-of-inspiration

- got-my-attention

- GlobeIsRound

- uInspireMe

- SoulSoother

- WordsWorthRetweeting

- SpiritFuel

What I’m trying to get across to you, @HolyWords, is that you have some pretty impressive stats for an account that has a mere 20,000 followers.

And, if that’s not inspiring enough for you, how about the fact that there are celebrity tweeters with millions of followers who not only read your daily tweets, but have favorited them and retweeted them to their own followers.

I’m sure there are more celebs following you then are listed here, but I was able to confirm these:

- @TheEllenShow

- @JessicaSimpson

- @RainnWilson

- @4EverBrandy

- @MsLaurenLondon

- @TiaMowry

- @QuietStorm32 (Chicago Bulls’ CJ Watson)

- @MissMya

- @ThisIsNivea

- @PaulWallBaby

- @DonteStallworth

The bottom line is we want you back.

So, I am asking all @HolyWord lovers to send an @ message from your Twitter account requesting more tweets.

I’m going to post this one on my timeline tonight:

@HolyWords >>

We love you, Soul Food…

…and we’re hungry 🙂

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 16, 2010 | "race", activists, celebrities, immigration |

If you’re an avid Desperate Housewives watcher, you know that Eva Longoria’s character, Gabrielle Solis, is currently tangled in a heart-wrenching storyline involving a past hospital baby switch. Gabby’s daughter Juanita is not biologically hers, but is the “anchor baby” of an undocumented Mexican couple who are now on the run with Gabby’s biological daughter (whom they raised from birth). We have yet to see where this plot is headed, but according to US law, Juanita could be taken to Mexico if her bio parents are deported.

In real life Longoria has been very vocal about immigration issues, and it appears that the writers are helping her use the show to bring attention to the serious plight undocumented children face. The actress has also recently donned the executive producer hat for the upcoming documentary “Harvest,” a film exposing the exploitation of migrant children who pick produce on American farms at sub-poverty wages.

“We won’t take a shirt made in China by a child, but yet in our own country 25% of the food we eat is harvested by a child…Over 500,000 kids are working in the fields and 80 to 90 percent are American children. We have these mixed-nationality families…How does immigration reform address those kinds of families?” -Eva

This morning Longoria joined a group of Latino leaders in addressing a letter to the leadership of the US Senate urging them to pass the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act). If passed, the legislation would provide a path to citizenship for children who were brought illegally to the United States by their parents.

December 16, 2010

Dear Senators Reid and McConnell:

As Latino leaders in government, business, entertainment, and sports, we urge members of Congress to support the “Development, Relief, and Education of Alien Minors (DREAM) Act.” This modest and sensible piece of legislation would allow young people who were brought to the United States by their parents at a very young age to pursue higher education or serve in the military.

These students are success stories in their communities, serving as student body presidents, star athletes, and performers, graduating often with honors from schools in their hometowns. Our country benefits immensely from the talent and drive to succeed that they demonstrate. They want the chance to go on to college or serve in the military to continue giving back to the only country they have ever called home.

We know from a recently released study that the students covered under the “DREAM Act” will contribute at least one trillion dollars to the American economy over the course of their lifetimes. Moreover, according to the Congressional Budget Office, enacting the “DREAM Act” would reduce the deficit by $1.4 billion dollars over ten years. The intangible benefits of investing in these students’ futures, however, are immeasurable.

America cannot afford to lose another generation of young people who stand to contribute to its economic and social prosperity. The beneficiaries of the “DREAM Act” are our future teachers, nurses, and engineers. The U.S. has invested in the education of many of these individuals since kindergarten, and it is only fitting that we enable them to serve and contribute, allowing our nation to reap the benefits. The Latino community is counting on Congress to come together and show its support for the future of these young people and the nation.

Sincerely,

Luis Castillo

Linda Chavez

The Honorable Henry G. Cisneros

Maria Contreras-Sweet

Emilio Estefan

America Ferrera

The Honorable Carlos Gutierrez

Eva Longoria

Monica Lozano

Janet Murguía

Ozomatli

The Honorable Federico F. Peña

The Honorable Bill Richardson

Lionel Sosa

Solomon D. Trujillo

The Honorable Antonio Villaraigosa

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 15, 2010 | activists, against the odds, barack obama, education, entrepreneurs, heroes, i rave, that's LOVE, they give, transformation, young people |

I mean no disrespect to Geoffrey Canada’s wife, but her husband is my idea of what a real man looks like.

I mean no disrespect to Geoffrey Canada’s wife, but her husband is my idea of what a real man looks like.

Okay, okay, before I get myself in too much trouble, let me clarify that in using the term “sexy” to describe this married father of six, I am respectfully referring to the non-erotic definition: “arousing intense excitement.”

Just so you know, I’m not the only person in the world admitting to being intensely excited by the man. Geoffrey has aroused the ardor of a diverse body of media personalities including David Letterman, Ed Bradley, Stephen Colbert, Anderson Cooper, Oprah Winfrey and Glenn Beck. When Oprah first laid eyes on him she flung her arms wide for a hug and gushed, “I just want to kiss you.” (I’m feeling you, O.)

The President of the United States called Canada “a pioneer…saving a generation of children.” First lady Michelle Obama referred lovingly to him as “one of my heroes,” and an award-winning documentary about him entitled “Waiting for Superman” (yes, that is a reference to Geoffrey) was released this fall to critical acclaim.

If you’re not up on what this man does for a living, I’m going to have to let you Google that, because as ambitious and awe-inspiring as it is, I am on a more personal mission here. Here’s the short version of why he’s garnered so much attention:

Geoffrey Canada’s Harlem Children’s Zone is transforming a 97-block area into a community of stakeholders whose primary focus is educating the program’s 8,000+ (mostly poor) children to such high levels that 100% of them will graduate from college. (Yes, you read that right.)

What Mr. Canada does is undoubtedly worthy of great respect and praise, but why he does it should also be the subject of a documentary as far as I’m concerned. What motivates a man with a Master’s Degree from Harvard to invest it in Harlem? We can easily observe that he shows incredible passion and tenacity in pursuing quality education for all, but what exists deep down in the man that leads him to devote his life to saving other people’s children?

Geoffrey says the calling to serve his community rang in his ears at a very young age–on one of the saddest days of his life.

“…my mother told me Superman did not exist.”

He cried.

“I read comic books and just loved them because even in the depths of the ghetto you thought, ‘He’s coming, I just don’t know when, because he always shows up and he saves all the good people’.”

Geoffrey’s mother thought he was crying for the same reason a child mourns upon learning that Santa Claus is not real, but even at such a young age, he knew his loss of Superman had devastating implications.

“I was crying because there was no one coming with enough power to save us.”

Some fifty years later, while most of us stand around arguing about whether it is poor leadership, ill-prepared teachers, uninvolved parents, disinterested students, or a multitude of other excuses for why millions of children are being academically shortchanged, this man chooses to focus instead on high expectations and successful solutions.

The urgency he feels about educating children is reflected in this excerpt from a poem entitled “Don’t Blame Me,” written by Canada in 2007.

If there is a God or a person supreme,

A final reckoning, for the kind and the mean,

And judgment is rendered on who passed the buck,

Who blamed the victim or proudly stood up,

You’ll say to the world, “While I couldn’t save all,

I did not let these children fall.

By the thousands I helped all I could see.

No excuses, I took full responsibility.

No matter if they were black or white,

Were cursed, ignored, were wrong or right,

Were shunned, pre-judged, were short or tall,

I did my best to save them all.”

And I will bear witness for eternity

That you can state proudly,

“Don’t blame me.”

I love this super man.

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 14, 2010 | activists, africa, aids / hiv, celebrities, life after loss, parenthood, remembering you, they give |

“Being a princess isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.” -Diana, Princess of Wales

If you’re like me, that whole Disney-style princess thing is one huge turnoff. I mean really, what self-respecting mother is going to teach her daughter that the ultimate happily-ever-after comes from catching the eye of a handsome prince and getting lucky enough to sit next to his throne for the rest of her life?

Uh, no. I don’t think so.

I’m way more excited about Tinkerbell and her little fairy BFFs who are adorably flawed (Tink has a bit of an anger management problem), are able to acknowledge the awesomeness of their individual gifts, and proudly use those gifts to make the world better for everyone.

It makes perfect sense to me that Diana Princess of Wales was, and remains, so incredibly adored worldwide. Diana was never content to simply be Prince Charles’ wife, but instead chose to behave more like a fairy princess, refusing to pretend she was flawless, and flying around the world using her powers to relieve human suffering–while encouraging us all to be more loving.

“Nothing brings me more happiness than trying to help the most vulnerable people in society. It is a goal and an essential part of my life.” -Diana

When she died the world lost a true philanthropist, and her two young sons lost a loving mother and role-model who was teaching them by example how to use their royal positions to serve others.

“I will fight for my children on any level so they can reach their potential as human beings and in their public duties.” -Diana

Just 12 and 15 when they lost her, Diana’s influence on the boys did not fade as they matured. Both princes are now known for their humble and friendly approach to the public, and both have upheld their mother’s legacy of philanthropy by contributing time and money to HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, wildlife preservation, environmental protection, the inner-city disadvantaged, the homeless, and African poverty relief. Harry is co-founder of Sentebale, a joint effort with Prince Seeiso of Lesotho to help meet the needs of children orphaned by AIDS . Diana’s sons have honored their mother by serving those she would if she were here–underscoring their strong belief that the dead continue on in another life and guide those they left behind.

“I’m aware that people I have loved and have died are in the spirit world looking after me.” – Princess Diana

Though she died over 13 years ago, Diana’s legacy as devoted mother of these two grandsons of Windsor (who are second and third in line for the throne) has recently become the topic of much conversation, as her eldest William just announced his engagement to his longtime girlfriend Kate Middleton. William proposed to Kate a few weeks ago while in Kenya, offering her the sapphire and diamond engagement ring his father Prince Charles had given his mother.

“She’s not going to be around to share in any of the fun and the excitement…so this is my way of keeping her sort of close to it all.” -Prince William

The wedding will take place in late April, not long after Mothering Sunday (the UK version of Mother’s day), a day that is extremely painful for William. Last year he celebrated the holiday by announcing his patronage of the Child Bereavement Charity, an organization co-founded by his mother a few years before she died. After several private meetings with bereaved families, he spent time with a group of children who lost parents or siblings. He spoke candidly with the youngsters, referring to Mother’s Day as an occasion of sadness and emptiness, and describing a loss like theirs as “one of the most difficult experiences anyone can endure.”

“Never being able to say the word ‘Mummy’ again in your life sounds like a small thing. However for many, including me, it is now really just a word – hollow and evoking only memories.” -William

Those who cherish the memory of Princess Diana will be watching with excitement and hope as William and Kate begin their lives together as man and wife, and though I’ve never considered myself a “royal watcher,” I must admit I’m eager to see a few years into the future when the couple become parents, something William says they certainly plan to do. That is when Mother’s Day will be transformed from an excruciating occasion into a bittersweet celebration. When the day is spent honoring the mother of his children and reminiscing about the amazing grandmother they didn’t get to meet, I suspect Mothering Sunday will take on a new and much more joyful spirit for the prince.

God willing, Prince William will be able to say the word “Mummy” again soon, and when he hears it from the mouths of his little ones, he may find it holds a magical quality that, like Tinkerbell’s pixie dust, will lift him high above his pain.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NK3ODM5S0Lg]

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 13, 2010 | adopted, authors, celebrities, multi-ethnic, musical artist, transformation, unprotected sex |

I don’t know about you, but I’m a sucker for any story that at it’s heart is about transformation. I think that’s why I love HGTV so much–you know–the creativity and elbow grease and coordinating fabrics of it all.

I don’t know about you, but I’m a sucker for any story that at it’s heart is about transformation. I think that’s why I love HGTV so much–you know–the creativity and elbow grease and coordinating fabrics of it all.

Watching those funky old fixer-uppers being transformed into stunning new homes just gets me giddy. It’s like a metaphor of sorts for how hopeful we can all be about the caterpillar-to-butterfly potential we humans possess.

So, it’s no wonder Nicole Richie’s very public journey from awkward/wayward teenager to mommy/mogul/author/wife is my kind of true-life fairy tale.

In a town like Hollywood, where so many of the young up-and-coming are sidelined by alcohol and drugs, it was no real shock to anyone when Lionel Richie’s adopted daughter Nicole began her early slide into getwastedness (along with her then best friend Paris Hilton). At age 22 Nicole was arrested for DUI and charged with possession of heroin. By the time she was 25, she had racked up another DUI charge and was sentenced to jail time. She lost so much weight we all diagnosed her with an eating disorder (which she says was never true), and then, to make matters worse she (gasp) went and got herself knocked up by a rock star. Well, damn. Go ahead and throw in the towel on that little privileged chick, right? Not so fast…

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yINgnfkP24&fs=1&hl=en_US&rel=0]

Don’t tell Sarah and Bristol Palin I said so, but the best thing that ever happened to Nicole Ritchie was unprotected sex with Good Charlotte front man Joel Madden. Not that I’m advocating that for the average spoiled, out of control, rich reality television personality. Heavens NO. But I do think that becoming pregnant and being in a loving relationship with a man like Joel turned out to be a perfect storm that blew Nicole out of the fast lane and onto a path towards real maturity.

Nicole sat down with Robin Roberts in September to talk about her new, extremely busy life as the mother of two children, owner of four successful businesses, and author of two novels.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CB7zuwuhpVY]

On Saturday, December 11th, Nicole and Joel stood before Reverend Run at her father’s Beverly Hills estate and became husband and wife.

Congratulations to you and your family, Nicole. Your metamorphosis is nothing short of awesome, and I hope you never stop reaching for the sky.

Little known facts about Nicole:

- She was born Nicole Camille Escovedo

- She was blessed with two super-talented godfathers: Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones.

- Her clothing lines are named “House of Harlow” and “Winter Kate” after her daughter Harlow Winter Kate Madden.

- In February 2010 her Richie-Madden Children’s Foundation funded the development of a playground in Los Angeles to encourage children to get outside and play

- She plays cello, piano, and violin.

- She stands to inherit 200+ million from her father’s estate.

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 12, 2010 | against the odds, celebrities, entrepreneurs, i rant, they give, transformation |

Me on Oprah’s show, 1994

Let’s suppose for a moment that we all agree on the following premise: The purpose of life is to

- Love and be of service to others

- Develop one’s own emotional, intellectual, creative and spiritual potential to its fullest

- Positively influence the emotional, intellectual, creative and spiritual growth of others

- Leave the world a bit better than it was when you arrived

(You’ve probably noticed the list doesn’t include anything that refers to allegiance to a specific religious figure. That one is between you and your Creator, so we’ll leave it closed to outside scrutiny.) I don’t know where you are on your list, but, um… Well, let’s just say I hope I have at least another 50 years or so left to work on mine, ’cause I’ll likely need every second of that time to accomplish even 1% of what Oprah Winfrey (who was born to a single teen mother and raised in a house with no electricity and no running water) has in her 50+ years. (But hey, maybe I can get a little extra credit for having raised a houseful of kids with little assistance from my ex-husband.) When you are at the helm of an empire as gargantuan as Oprah’s, it is a given that you will have sacrificed much in your personal life along the way. After watching her recent interview with Barbara Walters, I have gained a profound respect for Oprah’s dedication to perfecting her craft, and her unbelievable work ethic–but I find myself wishing that she and Stedman had produced some children. With the kind of career ambitions Oprah held from a young age, I can completely understand why she didn’t feel like motherhood was her path, but it just seems impossible to me that she and Stedman wouldn’t have raised some beautiful kids that would have added value to the world. I know, I know, what happens or doesn’t happen in the woman’s womb is none of my business, but as with all public figures, it’s always tempting (and easy when you’re not in their shoes) to speculate on what they should or should not do with whatever they’ve got. Despite the fact that Oprah is tested on a daily basis with the kind of wealth and power that would turn many of us into self-aggrandizing heathens with little concern for the lives of others, I would venture to say the number of souls she’s purposely helped (so far) in her lifetime far outweighs any she’s purposely hurt, and despite the fact that her “brand” generates billions in corporate profits, the legacy she’ll leave when she’s gone will certainly be one of inspiration, transformation and personal growth. And, according to Oprah, she’ hasn’t even really gotten started yet. When asked by Barbara if she felt like she’s accomplished the greatness she was born to, Oprah replied,

“I feel that I’m still in process…as great as the past 25 years have been–just astounding, I mean really the word ‘AWEsome’ does apply–I think it was just the beginning.”

I was a guest on Oprah’s show many years ago, which impacted my writing life and my career in countless ways I won’t go into here, but I’m not one of those Oprah worshipers who believe she walks on water (if that were possible, believe me her producers would have already made a show about it). No. Oprah’s no saint. The woman is certainly flawed, as all of us humans are, but it amazes me how many vicious haters she has in the world. I mean, really. Give the woman a friggin’ break already. Frankly, I’m not sure what kind of person I’d be if I was worth 2.3 billion. (Not that I wouldn’t like to find out.) If you didn’t get a chance to watch the Barbara Walters’ interview, I have posted it below. (Thank you to CelinishAnime for uploading the 5-part interview to YouTube for our viewing pleasure.)

[embedplusvideo height=”402″ width=”500″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/A_MsmbERGmg?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=A_MsmbERGmg&width=500&height=402&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5638″ /] [embedplusvideo height=”402″ width=”500″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/geIWGJ12vQ4?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=geIWGJ12vQ4&width=500&height=402&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep7975″ /] [embedplusvideo height=”402″ width=”500″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/axSN0cyu8Dg?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=axSN0cyu8Dg&width=500&height=402&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep8195″ /] [embedplusvideo height=”402″ width=”500″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/WMgZ5fFae1s?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=WMgZ5fFae1s&width=500&height=402&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep4038″ /] [embedplusvideo height=”402″ width=”500″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/7Un1LKbpCAg?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=7Un1LKbpCAg&width=500&height=402&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep3630″ /]

by Kathleen Cross | Dec 12, 2010 | Uncategorized |

I hate to admit this, but I read Internet gossip blogs just about every day. I have a folder on my Google Chrome toolbar with eleven gossip sites I visit regularly. A few of them I would loosely describe as “journalistic,” that is, although they are made up of “celebrity news,” (mostly none of our business) they’re pretty careful not to print unsubstantiated rumors. However, several of the very popular gossip blogs are really just irresponsible rags that revel in dragging celebrities through the mud–those blogs will print any story (or non-story) they think might land them on Twitter’s trending topics list.

To justify my daily wade through the filth, I tell myself I’m visiting these sites to investigate whether any of my friends, family, acquaintances or favorites in the entertainment industry are being gutted or glorified that day (who died and made me the blog police, right?) But, the reality is I’m just like every other gossip blog reader who is looking for the latest tidbit of juicy scandal that might be, but probably isn’t, true. Of course, I give myself credit for knowing I can’t believe most of what I’ve read (which I’m sure to announce right before I share it with a friend). :/

Though I can’t say I’ve stopped visiting them altogether, lately I’ve discovered that I’m reading fewer and fewer of the more scandalous stories on these blogs, and am instead scrolling through the headlines to find something positive to read. On the rare occasion that I do come across a positive or uplifting story, I really appreciate it–it’s like I’ve discovered a rose among the thorns feces.

I don’t think I’m particularly “holier” than anyone else, so I’m not trying to put myself above it all. I’m just wondering if there are other readers out there who would appreciate not having to scroll past “NBA baller’s new wife joins his baby mama to beat up his jumpoff” to find something a tad more inspiring.

If you’re out there, this blog’s for you.

by Kathleen Cross | Aug 16, 2008 | Uncategorized |

Calling a few adventurous anti-racists…

I am conducting an experiment, and I need the help of ten people of various ethnic backgrounds who are willing to participate.

The experiment will simply entail wearing a (free) t-shirt that features a photo of an abolitionist hero with the message “I’ll choose my own heroes, thank you.” Participants must agree to post about reactions to the shirt.

There are two different t-shirts in the experiment. Both feature white American abolitionists. One of the t-shirts features a picture of John Brown , the other a picture of James and Lucretia Mott. See samples of each shirt below.

Of course, the text on the shirt would indicate that the individual depicted there is indeed someone you would choose as a hero — if that is not the case, you would not be an appropriate candidate for this experiment. I am looking for participants who would choose John Brown and/or James and Lucretia Mott as individuals they would refer to as heroes.

The shirt is free to ten selected participants who write to me at novelistkc@gmail.com Please include a brief paragraph about your interest and/or involvement in anti-racist issues, indicate your ethnicity(ies), and tell me why you are interested in this experiment. Also please include a mailing address, and indicate which of the shirts you would prefer (and why).

Front of John Brown T-shirtBack of John Brown T-shirt

Back of John Brown T-shirt

Front of James and Lucretia Mott T-shirt

Back of James and Lucretia Mott T-shirt

by Kathleen Cross | Jul 20, 2008 | Uncategorized |

Did you know there was a white woman who was murdered by the Klan because of her involvement in the American Civil Rights Movement?

Viola Liuzzo with her children

Did you know she was a wife and mother of five children?

Did you know that among her last statements to her husband before she died was that the struggle for civil rights for black Americans was “everybody’s fight?”

Did you know the day after she was murdered, President Lyndon Johnson called her husband Jim to say, “I don’t think she died in vain because this is going to be a battle, all out as far as I’m concerned,” and Jim responded, “My wife died for a sacred battle, the rights of humanity. She had one concern and only one in mind. She took a quote from Abraham Lincoln that all men are created equal and that’s the way she believed.”

That woman was Viola Liuzzo (1925-1965). She sacrificed her life for Civil Rights.

Viola Fauver Liuzzo belonged to the NAACP at the height of the civil rights movement. In 1965, she marched with Martin Luther King from Selma to Montgomery. After the march, Liuzzo and her black co-worker, Leroy Merton, shuttled marchers to the airport. They were spotted by four Ku Klux Klansmen (one of whom was on the FBI’s payroll) who followed the pair and shot them. Liuzzo died instantly. Merton survived.

Can someone explain to me why this woman’s photograph isn’t on the wall in every classroom in America?

Please read the article below. Viola Liuzzo once said to a friend “…You and I are going to change the world. One day they’ll write about us. You’ll see.”

They did write about her. Now, if only more folks would read about her, she may get the hero status she deserves:

Viola Liuzzo: ‘We’re going to change the world’

By Minnie Bruce Pratt

Published Mar 2, 2005 1:49 PM

After years, decades, centuries of struggle, the Black civil rights movement celebrated one of its greatest triumphs on March 25, 1965. On that historic day, some 25,000 pro testers of all nationalities marched into Montgomery, Ala.–a former capital of the slave-owning Confed eracy in the 19th century.

The protesters were completing a four-day march from Selma, Ala. An attempt to march the same route earlier in the month to protest the Feb. 18 killing of African American voter-rights activist Jimmy Lee Jackson had been met with intense repression. On Sunday”–March 7, 1965–Alabama state troopers on horseback had tear-gassed and mercilessly clubbed 600 women, men and children as they marched peacefully across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Viola Liuzzo

After this outrage, civil-rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King sent out an appeal across the country for all who supported the African American freedom movement to come to Selma.

One of the thousands who answered that call was Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old white woman from Detroit. On the evening of March 25, as she was ferrying an African American marcher back to his home in her car, a carload of Ku Klux Klan members forced her car off the road, shot and killed her.

Liuzzo was the only white woman to give her life during the Black civil-rights movement of the 1960s. With that sacrifice, she joined a handful of white men, like the Rev. James Reeb, killed in Selma earlier the same month.

She also joined the hundreds of thousands, the millions, of known and unknown Africans and African Americans who had fought and died for their freedom—from the 40 who fell in battle against South Carolina slave owners at Stono River in 1739, to Jimmy Lee Jackson. Jackson, a 27-year-old farm laborer and pulpwood cutter, who was shot down on Feb. 18, 1965, at a voter-rights protest in Marion, Ala., as he attempted to protect his mother and grandfather from the clubs of the state troopers.

A recently released film, “Home of the Brave,” dir ected by Paola di Florio, attempts to document Liuzzo’s life and legacy. It does give a glimpse into the background of this almost unknown anti-racist fighter, but without fully exploring all the forces that shaped her.

Courage in the struggle

What experiences led Liuzzo to reject racism and segregation, and to journey South into struggle?

She was born in 1925 into a coal-mining family in Pennsylvania. Her father made 50 cents a day when he could find work. He received no compensation from the mine owners after he lost a hand in an accident. As the family quickly sank into poverty and moved from town to town through Tennessee and Georgia, Liuzzo saw firsthand the violence and degradation of racism toward African Americans.

During World War II the family moved North to find jobs. Her father worked at a bomber plant in Ypsilanti, and her mother at a Ford plant in Detroit. Liuzzo found wartime work in a cafeteria, married, and became close friends with Sarah Evans, an African American woman through whom she joined the NAACP.

Liuzzo organized locally for an end to discrimination in education and for economic justice. She was arrested twice and insisted on a public trial to bring attention to these causes. (Joanne Giannino, Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography)

According to Liuzzo’s daughter, Mary Liuzzo Lilleboe, “My mother was raised in the South and she followed the whole labor story.” She noted that the FBI files from the investigation of Liuzzo’s death show Liuzzo wrote letters “to protest the government’s witch-hunt of the labor unions.”

Liuzzo resisted her oppression as a woman as well. When she went back to school as a high-school dropout, working-class housewife and mother of five, she wrote, “I protest the attitude of the great majority of men who hold to the conviction that any married woman who is unable to find contentment and self-satisfaction when confined to homemaking displays a lack of emotional health.”

After the death of one of her children at birth, she broke with the Catholic Church because it decreed that unbaptized babies spend eternity in “limbo.” She joined a local Unitarian Universalist Church where many of the members had been Freedom Riders in an earlier struggle against segregation in public transportation.

In an interview, Evans later said of her friend: “Viola Liuzzo lived a life that combined the care of her family and her home with a concern for the world around her. This involvement with her at times was not always understood by her friends; nor was it appreciated by those around her.”

Smearing a radical

After Liuzzo’s death, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover began a smear campaign against her. She was red-baited and accused of sexual immorality, in particular with African American men.

An FBI informant, Gary Rowe, was implicated in her death. He was in the car on the night of her killing with Klan members subsequently charged with her murder. The three Klansmen were acquitted by the state, but later served 10-year federal sentences for violation of Liuzzo’s civil rights. Rowe was never charged for any crime and escaped into the Federal Witness Protection Program.

Of the Liuzzo documentary, director di Florio observed: “I experienced my own loss of innocence. It hadn’t occurred to me before making this film that reckless collection of data, inconsistent accounts of the incident, and flat-out lies about Viola Liuzzo could all be part of ‘official documents.’ As I began to meet with leaders in the field of government, politics and history, I realized that this was quite common, in fact. What happened to Liuzzo could happen to any of us.” (Emerging Pictures)

Di Florio’s film shows Liuzzo’s life and also focuses on her legacy. Unfortunately, the documentary dishonors Liuzzo’s sacrifice by implying that her death and the smear campaign that followed somehow led her sons down a reactionary path. The youngest, Tony, became second in command of the Michigan Militia. The oldest, Tommy, joined white “survivalists” in Alabama. The film shows an effigy meant to represent an

African American hanging from a noose in their campground.

This is truly heart-wrenching information, given that one of the most touching scenes in the documentary is the TV footage shot immediately after Liuzzo’s death, when 14-year-old Tommy says to reporters, “She wanted equal rights for everyone, no matter what the cost!”

But the film doesn’t explore the larger economic and social factors that inexorably shape the lives of every child in her or his own historical period, no matter what their parents’ politics.

Liuzzo’s legacy

Liuzzo’s oldest daughter, Mary Lille boe, offers the beginning of an explanation more rooted in the material reality of workers’ lives: “The issues we face are well beyond the immediate. Both the Demo crats and Republicans are capitalist and are wrong. I know this lesser-of-two-evils argument and I think it is very narrow in its vision….

“We saw what the government was capable of doing when it felt threatened by what my mother stood for. The organizations that were supposed to defend workers did nothing. The militias developed because workers, like our family, were abandoned.”

“We need something new. Socialism is a dirty word in this country because it threatens people at the top. I don’t think it’s an accident that people today are attracted to my mother’s story.”

Liuzzo herself was full of hope, and conscious that the future would include more than just her story.

According to Sarah Evans, Liuzzo would often say: “Sarah, you and I are going to change the world. One day they’ll write about us. You’ll see.”

It is worth noting that “Home of the Brave” gives no details of Sarah Evans’ political life or history.

Di Florio’s documentary does not show Liuzzo’s vision, or her understanding that the struggle was more than her individual story.

One scene from the documentary captures the necessity of the continuing fight to secure the most basic democratic rights for oppressed nationalities in the United States. At a voting site in Selma during the 2000 election, a Black poll worker sits at a table side by side with an older white poll worker. The latter is asked what he remembers of Viola Liuzzo, and answers after a sour look that he doesn’t think a woman like that should have come to Selma.

The Black man turns to the camera and says that he feels that Liuzzo was a fine woman. And one image of Liuzzo lingers in the mind’s eye: a photograph of her in the line of march, a few miles from Montgomery. She is walking barefooted, carrying her shoes, looking ahead, completely focused on the goal of freedom.

________________________________________

This article is copyright under a Creative Commons License.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email: ww@workers.org

Subscribe wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news http://www.workers.org/orders/donate.php)

by Kathleen Cross | Jul 12, 2008 | "race", anti-racist, heroes, i rant, privilege, seriously?, slavery, stereotypes, transformation, young people |

I was returning home to Los Angeles on a flight from Atlanta, where I’d spent a couple of days at a writer’s conference.

I was returning home to Los Angeles on a flight from Atlanta, where I’d spent a couple of days at a writer’s conference.

Weary from a weekend filled with late night poetry jams and early morning workshops, I boarded the half-empty redeye, found my aisle seat, shoved my bulging carryon bag under the empty middle seat, stretched my legs and thanked the airline gods for arranging an entire row just for me.

I closed my eyes as the last few stragglers made their way to their seats, and got an early start on what I hoped would be a long nap.

“Excuse me, Ma’am.” The voice was deep, the accent, southern.

I opened my eyes to an attractive white man in his early twenties looking down at me. He pointed at the empty seat next to me, shrugged a sheepish apology, and stepped back to let me stand, which I did. He didn’t take the empty window seat. Instead, he plopped his duffel bag near the window and sat himself down right next to me, which meant, of course, that I would have to move my bag.

I reached down and tugged at the strap, but my tightly wedged carryon didn’t budge. “I’ll get that,” he offered. He yanked the bag out, slid it to me and helped me squeeze it under the seat in front of me. It didn’t occur to the guy to just move over to the empty window seat. He flashed a perfect soap opera star smile at me, stowed his bag under the window seat and stretched his legs.

“Hey, what’s this?” He bent over to reach for something on the floor in front of him and came up with an award I had been given at the conference. He read the inscription aloud, “Best Contemporary Fiction,” then looked me over. “Wow,” he said with a raised eyebrow. His expression said my sporty pink jogging suit and Adidas cross trainers didn’t jibe with his vision of what an award-winning author might look like up close. “You’re a writer?”

There goes my nap. I knew in that moment I would spend my five-hour flight locked in conversation. It was inevitable. He would ask me what my book was about and as soon as I said, it’s a novel about a woman who’s half black but looks white,” he would take note of my ivory skin and blue eyes and realize, correctly, that I wrote the book from my own experience. Then the questions would start.

“You’re black? Wow. You don’t look it.” He was immediately intrigued, as are most white people when they meet me. I haven’t completely figured it out, but I suspect their fascination has to do with my apparent whiteness and my paradoxical belonging in the black community (where the majority of people who look like me feel anything but a sense of belonging).

Just as black people often joke that I am a spy infiltrating the white ranks, I suppose white people see me as an insider to the black world—an undercover comrade who can interpret what I’ve seen and experienced in ways they can relate to. That’s the only explanation I have for the ridiculous comments some white folks make when they discover my dual ethnicity.

In addition to the many off-the-wall questions I’m asked (Can you dance like a black person? Why don’t black people swim? Is that penis size thing really true?), white people say things to me they would never say to a more phenotypically obvious black person. For instance, I once had a white woman refer to the black man she had recently stopped dating as “too black.” When I asked what that meant, she explained matter-of-factly, “He’s ignorant and has no ambition.”

In my younger days I bristled at these exchanges, but as I’ve grown older I’ve come to the conclusion that each time I respond to these ignorant questions and statements with some degree of patience, the world becomes a slightly better place. In most cases I find that the decision to practice patience has a positive affect on the outcomes of these exchanges—including the impending conversation with the middle seat taker.

After he introduced himself as Jason, an actor on his way to Hollywood to audition for (who woulda guessed it?) a soap opera, he tugged and nudged me into a conversation that can best be described as Everything Jason Ever Wanted to Know/Say About Black People But Was Afraid to Ask/Get His Ass Whupped. He began the discussion by saying with wide-eyed sincerity, “I don’t have a racist bone in my body.” He punctuated that idea by adding that he had “even dated black girls.”

While the other passengers slept soundly, Jason and I struggled to keep our voices at a half-whisper as we discussed topic after touchy topic. We talked about the overrepresentation of black people in the criminal justice system. Jason chalked it up to the “fact” that black people are more likely than whites to use illegal drugs. I countered with a government study that found 75% of regular drug users were white and only 8% black; yet 43% of those imprisoned on drug charges were black, and 25% were white. Of course, at the root of that is the fact that blacks are five times more likely to be targeted for arrest than whites for drug crimes (Source: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services.)

Jason and I discussed the underrepresentation of black students in college. He believed that was “of course” because black kids and their parents don’t value education. I explained that the best predictor of college entry and success is the quality of middle and high school curriculum. White high school students are three times more likely to be taught challenging coursework as blacks and twice as likely to be taught by an experienced teacher with specific expertise in the subject being taught. (Source: The Education Trust, “Achievement in America”)

We talked about interracial marriage. Jason will date, but couldn’t see himself marrying a black woman, though in his experience he found “mixed” kids to be more beautiful and more intelligent than “regular” black kids—a comment that I, being “mixed” was supposed to have taken as a compliment. Of course my counter argument for that ridiculousness was a thorough lesson on white supremacy and how it permeates everything in America – including how we arrive at our decisions about who is “beautiful” and who is “intelligent.”

Although there were many tense moments in our conversation, during which I had to struggle to maintain my calm, by far the most excruciating subject for me to endure was the one we spent over two hours entrenched in—slavery. I was astounded by Jason’s ignorance of the institution itself. Not only did he reiterate my elementary school teacher’s beliefs about slaves being relatively happy family members, he went so far as to repeat a joke he’d recently heard on a talk radio show which callously declared that American blacks shouldn’t be worrying about reparations, but “ought to be happy we aren’t charging them for their ancestors’ cruise over here.”

Jason seemed (keeping in mind he’s an actor) to have no idea that the Middle Passage constituted a holocaust of unprecedented proportions. Even conservative estimates place the number of slaves who died of abuse, disease, suicide and malnourishment during the Atlantic slave trade in the millions. The “cruises” Jason spoke of were months-long torturous voyages during which the “passengers” were chained to one another on stacked wooden bunks with less than a foot of space on either side. The kidnapped Africans who managed to survive day after day of writhing in blood, vomit, menstrual flow and excrement were delivered to the auction block and sold to the highest bidders. Women and girls had no defense against rape and were mated with men they did not know so they would produce children over whom they had no parental rights. Happy to be slaves? I don’t think so.

When confronted with that reality, Jason didn’t think so either.

What was most disheartening to me was that at his age, and with the advances in “multicultural education” this nation has supposedly made a commitment to, I expected the information I was sharing with Jason to have been taught to him in school. I told him about my experience with my elementary teacher Miss Lewis some thirty years previous—about her insistence that her heroes were good people who behaved in accordance with the times in which they lived; about her ignorance of the many anti-racist Americans who did live during those times but did not uphold the status quo; I talked to Jason about how I was impacted as a child by my teacher’s refusal to denounce slavery.

Though Jason was educated two decades after me, he said he had received the same messages my teacher delivered to me. He knew that Thomas Jefferson and George Washington owned slaves, but when I asked him whether America’s most revered historical icons were racists, his answer was a safe, “I don’t know. It seems like it.” When I reminded him that America was “the Land of the Free” whose credo is “Liberty and Justice for All,” and whose currency is embellished with the phrase “E Pluribus Unum” (Out of Many One) he admitted that the heroes he was taught to admire and emulate did not live up to those ideals.

When asked to name a white American historical figure other than Abe Lincoln who sacrificed life, liberty or livelihood on behalf of human rights for all people, he could not offer Thomas Paine, John Brown, James and Lucretia Mott, Thaddeus Stevens, Henry David Thoreau, John and Jean Rankin, John Howard Griffin, Penny Patch, Viola Liuzzo, or any of America’s other thousands of white anti-racist heroes. WIth the exception of Lincoln, whose commitment to human rights has been furiously debated by historians, Jason had not one anti-racist role model he had ever been taught to look to for education or inspiration.

Upon our arrival at LAX, Jason said our conversation was one that forever changed him. He thanked me for challenging him to think more deeply about his responsibility—not just to denounce racism, white privilege and white supremacy, but to educate himself about it and to be a part of dismantling it. I hope Jason wasn’t pretending, but even if he was, it was that five-hour interaction with a young white man I would not see or speak to again that stands as one of the most frustrating, at times infuriating and ultimately inspiring conversations about black/white race relations I’ve ever experienced.

It was a conversation that sparked the idea for the book I’m currently working on — a learning tool where young people might come to “Know Good White People.”

by Kathleen Cross | Jun 30, 2008 | activists, anti-racist, heroes, human unity, i rant, i rave, money matters, slavery |

LUCRETIA AND JAMES MOTT ARE MY HEROES!

Imagine you lived during a time when the clothes you wore were produced by slave labor. Oh… wait… that’s right… if you’re the average American, (or the average Earthling for that matter) it is highly likely that at least one of the garments you’ve worn in the past week (perhaps what you have on right now) was produced by a worker who earned far less than a living wage. For evidence of this, please read the story below:

Indian ‘slave’ children found making low-cost clothes destined for Gap Kids

Child workers, some as young as 10, have been found working in a textile factory in conditions close to slavery to produce clothes that appear destined for Gap Kids… (click here to read the article)

Knowing this is widespread, and knowing that clothing is not something you can live without…

What would it take for you to commit to never again purchase or wear fabric or clothing that was produced unethically?

I asked myself that question today, and, to be honest with you, I haven’t arrived at a firm resolution yet. I want to change my life so that it mirrors what I know I believe, and yet I’m wondering how hard it might be to find and buy clothing that is cruelty-free. With the price of gasoline going sky high, and my budget already stretched to capacity, can I afford to forego inexpensive clothing for something that is guaranteed to have been produced justly? And then there’s the question of consistency. If I’m going to worry about how my clothing is made, shouldn’t I be worried about how my food is harvested? How about the furnishings in my home? At a certain point it becomes overwhelming — and that is probably why so many of us turn a blind eye.

Which is one of the many reasons I a.d.m.i.r.e. abolitionists Lucretia and James Mott.

In the decades leading to the end of legal chattel slavery in America, James and Lucretia Mott were fierce abolitionists who saw slavery as an evil to be opposed at every opportunity. Not only did they open their home to escaping slaves, the couple refused to use cotton cloth, cane sugar, and other slavery-produced goods.

Lucretia was known for her skill as an orator, and spoke publicly for abolition, despite repeated threats against her home and family.

African American Abolitionist Frederick Douglas wrote of Lucretia:

“Foremost among these noble American women, in point of clearness of vision, breadth of understanding, fullness of knowledge, catholicity of spirit, weight of character, and widespread influence, was Lucretia Mott of Philadelphia. Great as this woman was in speech, and persuasive as she was in her writings, she was incomparably greater in her presence. She spoke to the world through every line of her countenance. In her there was no lack of symmetry–no contradiction between her thought and act. Seated in an anti-slavery meeting, looking benignantly around upon the assembly, her silent presence made others eloquent, and carried the argument home to the heart of the audience.

I shall never forget the first time I ever saw and heard Lucretia Mott…The speaker was attired in the usual Quaker dress, free from startling colors, plain, rich, elegant, and without superfluity–the very sight of her, a sermon. In a few moments after she began to speak, I saw before me no more a woman, but a glorified presence, bearing a message of light and love from the Infinite to a benighted and strangely wandering world, straying away from the paths of truth and justice into the wilderness of pride and selfishness, where peace is lost and true happiness is sought in vain. I heard Mrs. Mott thus, when she was comparatively young. I have often heard her since, sometimes in the solemn temple, and sometimes under the open sky, but whenever and wherever I have listened to her, my heart has always been made better and my spirit raised by her words; and in speaking thus for myself I am sure I am expressing the experience of thousands.”

To learn more about Lucrtia and James Mott visit one of these links:

James and Lucretia Mott: Life and Letters By Anna Davis Hallowell, Lucretia Mott

http://www.gwyneddfriends.org/mott.html

As I read, and write about this awesome woman (and her husband who supported her work), I am inspired to get off the fence I’ve been on for so long. I pledge to educate myself about this issue and work to become a part of the solution.

I am a descendant of slaves whose forced labor produced goods that made rich people richer. Isn’t it a dishonor to them to buy or wear clothing that makes rich people richer at the expense of the disenfranchised and the desperate?

Here’s my poem about it:

For Us, By Us

kneel beside her now

this brown sister

sweat drenched

work weary

perpetually underfed

taste a drop of her sorrow

this Creator’s child

leg shackled

to desperation

freedom be her dread

ache to lift her burden

workhorse woman

baby tied

to bowed back

with rags from massa’s wife

scream out justice for this

soul survivor

hands weary

scarred and wageless

clinging to so-called life

we could end her slavery

invisible daughter

piece-worker

anonymous

sweatshop whore

call her name, haiti

dominca, mexico

she be nafta’s slave

serving two gods

hers, and, yes, brother, yours

condemn her masters

karan, levi,

brooks brothers

and, sadly,

your own f.u.b.u

hey, brother

she’s your sister

your daughter

your mother

hey,

brother

nice

suit

by Kathleen Cross | Jun 23, 2008 | Uncategorized |

I saw the film Traces of the Trade and was impressed most by its courage and its frankness. It is definitely interesting to watch the transformation of the family members as they begin to realize exactly what the term “slave trade” means, and how the buying and selling of human beings impacted their family legacy. I found it both intriguing and inspiring to see how the DeWolf descendants grappled with their “immoral inheritance”.

I see their journey as a metaphor for America herself.

Below are some photos from Tom DeWolf’s website Inheriting the Trade which is the title of his book that grew from his experiences during the making of the documentary. DeWolf describes his story as (in part) …”a story about the legacy of slavery and how it continues to impact relationships among people of different races today.”

I know I posted about this film last week, but since then, I came across this compelling article by Traces of the Trade filmmaker Katrina Browne, and had to share it.

By Katrina Browne | TheRoot.com

A filmmaker uncovers her family’s past as a Northern slave-trading dynasty.

June 20, 2008–Traveling the country while making a film, I’ve been struck by the fact that the vast majority of white Americans do not consider themselves “racist.” In the North, we especially presume ourselves innocent. I certainly did.

In 1995, when I was 28, and enrolled in seminary in Berkeley, Calif., I received a small booklet from my grandmother. She wanted to be sure her grandchildren knew about our family history. In the midst of stories about artists, writers, ministers and others in our family tree, she included a few brief sentences about our DeWolf ancestors being slave traders in Bristol, Rhode Island.

In researching the historical literature, I was horrified to learn that the DeWolfs, my ancestors, were actually the largest slave-trading dynasty in U.S. history. I don’t think anyone in my family realized the extent of it. The scope of the story had somehow been watered down over the generations. Our relatives, I learned, had developed this “vertically-integrated” model of smart capitalism applied to a cruel, horrific trade. They owned the ships, a rum distillery, bank, insurance company, several plantations in Cuba, and an auction house in Charleston, S.C.

Three generations of my ancestors brought more than 10,000 African people to Northern and Southern states and to the West Indies from 1769-1820 (that we know about for sure). They owned Cuban plantations for decades longer. But they weren’t alone. They were part of a broad-based pattern of Northern complicity in slavery. Average citizens bought shares in slave ships, back then, the way people buy shares in the stock market today. Workers made sails and ropes and shackles. Farmers grew food that fed sailors on slave ships and enslaved Africans in the West Indies. Not to mention that African people were enslaved in the North for over 200 years (how did I miss that in my history books?). And even when that practice ended, Northern textile mills used slave-picked cotton from the South to fuel the Industrial Revolution. And Northern banks and insurance companies kept the wheels in motion.

Receiving the booklet from my grandmother, I was shocked to hear this news about my family. But the bigger shock came in the very next instant: I suddenly realized that I already knew. I had completely buried this painful truth—pushed it far from my consciousness. I still don’t remember how or when I initially found out, but I have a friend who remembers me talking about it in college. The knowledge was clearly influencing me at some level: I had joined the (almost) all-black gospel choir at Princeton University, was devouring literature by black women authors, and in my 20s, I co-founded a multicultural Americorps program, Public Allies. White guilt was guiding me—but blindly, in a sense.

So rediscovering this family history in my late 20s told me a lot—it explained a lot. And discovering the vast extent of Northern complicity in slavery explained a lot, too. Parallel complicity and parallel amnesia, and some parallel white liberal guilt maybe?

I was seeing things more clearly now: Slavery was the foundation of the U.S. economy, South and North. Yet the North successfully constructed an identity as pure and heroic abolitionists to cover all this over. It’s understandable. No one wants to be related to bad guys.

But conscience gnaws at you. As I came to terms with the discovery, it also influenced my feelings about a broad range of social issues. If slavery was a national institution, I came to realize, then the legacy of slavery is a national responsibility.

Confronting this history and public policy questions about how to level the still unlevel playing field in this country isn’t just about confronting facts and figures. There is, of course, a tangle of emotions and narratives that need to be addressed.

While in seminary, I wrote a master’s thesis on Aristotle’s theories about the power of Greek tragedies to impact public dialogue. Theater and democracy went hand in hand in Ancient Greece. Important social issues—ripe for public debate—were highlighted in plays. I knew that the role of the North in slavery was a story I needed to tell, and that it should be a personal journey into the uncomfortable emotional terrain of my and my family’s relationship to the legacy of slavery. It needed to be told in an art form that can be experienced on a heart level and collectively; ideally with a chance to talk afterwards.

It became clear to me that creating a documentary film would allow me to show real people dealing with these real issues. I was inspired by Macky Alston’s documentary Family Name and Edward Ball’s book Slaves in the Family, which both came out in 1998. That was also the year in which Joanne Pope Melish released Disowning Slavery, which laid out New England’s “constructed amnesia” about slavery. And so, that same year, I resolved to make Traces of the Trade. Both Alston and Ball were descendants of Southern slave-holders, breaking codes of silence. I, a Northerner, had some truth-telling of my own to do.

I invited family members to accompany me to retrace the Triangle Trade on camera. I told them that as we traveled to Rhode Island, Ghana and Cuba to grapple with this history, that we should all be prepared to make mistakes, to embarrass ourselves as we felt—and perhaps fumbled—our way through the treacherous landscape of slavery, race and class. We’re human, and I wanted to humanize our attempts to face truth and get things right.

People of color I worked with in my 20s had said very directly that it was really important for white people to deal with our baggage with each other. They were tired of holding our hands through it all. It was a plea for us to do our homework, and then come back to the table. So on the journey, making the documentary, we held interracial dialogues in each country, but we also sequestered ourselves in hotel rooms, and talked, and talked, and argued and worked our way through things. Our family history is unique since it’s so extreme, but a lot of what we grappled with was just regular stuff about being white in America.

We argued, for example, about whether it was OK for us to attend certain events in Ghana that were part of a homecoming festival for people from throughout the African Diaspora.

Some of us, including me, felt that we should keep our distance, honoring the painful, sacred journeys that many African Americans were on. Others felt that we were risking being over-sensitive—walking on egg shells, bending over backwards, contorting ourselves out of our own humanity, our right to bear witness to the pain.

We showed rough cuts of the film to lots of people as we were making it, including white people with stories very different from ours. There is obviously a huge diversity in the “white community,” including many stories of struggle to make it in America. So people don’t want to feel like slavery and its legacy are their problem. There is this massive defensiveness and resistance to black anger and to calls for redress, and we felt that defensiveness in our discussions, large and small.

But the playing field is still unlevel. Every indicator shows it.

I’ve learned to trace back and connect the dots. Like to the fact that the federal government created programs such as the G.I. Bill that helped create the white middle class. Access to college education and home ownership is the bedrock for success in this country. Access that was denied to African Americans in the first half of the century has rippled to the present day. Hence, the vicious cycle back and forth of resentments, recriminations, tensions and distrust that manifest in small and large ways and keep the black/white divide painfully in place. Sen. Obama spoke so powerfully in Philadelphia about this “racial stalemate.”

It took nine years to complete Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North. As I watch it now, I am struck by the fact that none of us alive today created the profound mess, but we all inherit it. We inherit these mantles that lock us into roles: the “perpetrator” (be guilty or be defensive) and the “victim” (be passive or be angry). Our full human selves contain all those multitudes, as well as something above and beyond.

In the end, I hope the documentary invites Americans into heartfelt and honest dialogue on the core questions that still have such resonance in our society. What is the legacy of slavery—for European Americans, for African Americans and for all Americans? What would repair—spiritual and material—really look like? And what would it take…from all of us?

*****************************************************************************************

Traces of the Trade has its national broadcast premiere on Tuesday, June 24 at 10 p.m. on PBS’s P.O.V.documentary series. (Check local listings.) For further information on how to see the film and how to use it in your community: www.tracesofthetrade.org; www.pov.org.

My cousin Tom DeWolf was inspired to write a memoir of his experience of our journey. Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slave-Trading Dynasty in U.S. History, published by Beacon Press, is available now.

(Article courtesy of The Root: http://www.theroot.com )

by Kathleen Cross | Jun 18, 2008 | "race" |

(Photo: My father James H. Kelly | Great-great grandson of James Breeden and his “negro woman”

On February 28, 1825, a white Tennessee farmer appeared before the Hawkins County Court with his enslaved black woman and two children he sired with her, with the intention of petitioning for their freedom. As required by Tennessee law, James Breeden posted a bond of $500 (roughly equivalent to $9,000 today) so that he might be allowed to convince that body of white men that his “negro woman” and her offspring should no longer be considered his property.

Breeden’s argument apparently satisfied the court. Recorded that day was their decision:

“it is therefore considered…that said Negroes…be emancipated, freed and set at liberty.”

Thus, Charlotte Breeden was granted her freedom along with her two young sons, Lelan and Pleasant. When Pleasant reached adulthood he left Tennessee for Jerseyville Illinois where he purchased 40 acres of land, married a black woman named Cordelia Hinton and produced a free-born daughter, Charlottie Breeden, my great-grandmother.

As I am aware of the economic, social, educational, pyschological and other benefits received by my family, I can say without reservation that the act James Breeden committed before the court on that day more than one hundred and seventy five years ago was good, but I have no idea if he was. He did, after all, own my great-great-great grandmother.

I don’t know if James purchased Charlotte on an auction block, or inherited her from a relative — she might have been a gift from a friend, along with a wheelbarrow and some farming implements. Or, perhaps he bought her from an evil neighbor to save her from a life of torment. There is a heavy ache behind my ribcage as I ponder the possibilities, and concede to the reality that I do not, and probably cannot ever know.

Historical records indicate that James Breeden never married nor sired children with anyone other than Charlotte. In his will he provides for her upkeep,

“I will to my negro woman Charlott (that I have freed) one cow and calf for her support, also one sow and pigs to her own use.“